In the Americas, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in a context of high social inequality, generating negative synergies with other pre-existing epidemics. Several studies carried out in different countries of the Region have documented higher lethality among people residing in areas with a higher concentration of poverty, as well as among indigenous and Afro-descendant people (). The pandemic resulted in loss of human life, reductions in life expectancy, and simultaneous and synchronized impacts on physical, mental, and social health. This was especially severe in social groups in conditions of vulnerability.

Epidemiology

Between the appearance of the first cases of COVID-19 in the Region and 31 August 2022, five epidemic waves have been recorded (Figures 3.1 and 3.2). All have been characterized by differences in the virulence and lethality of the disease. The latest wave has been contained thanks to COVID-19 vaccination coverage, which has contributed to a significant reduction in mortality (,).

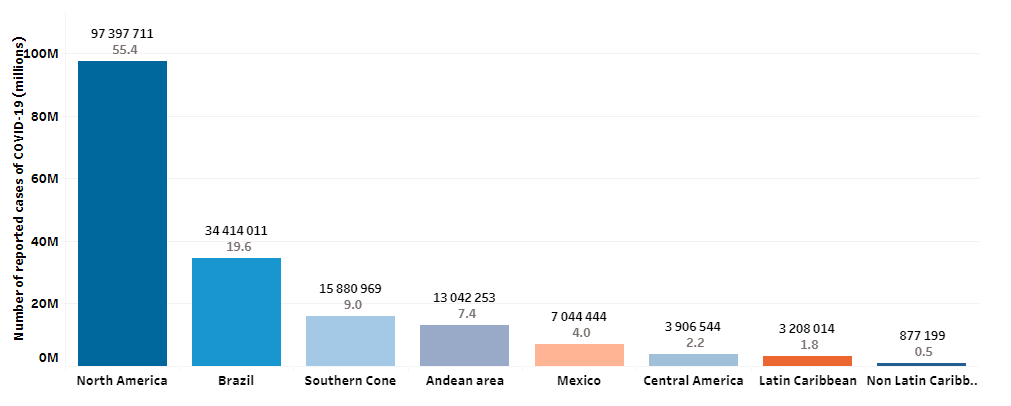

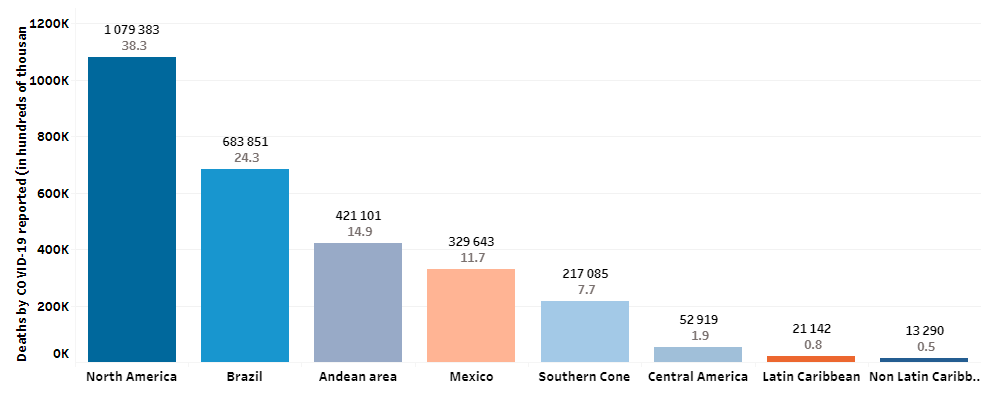

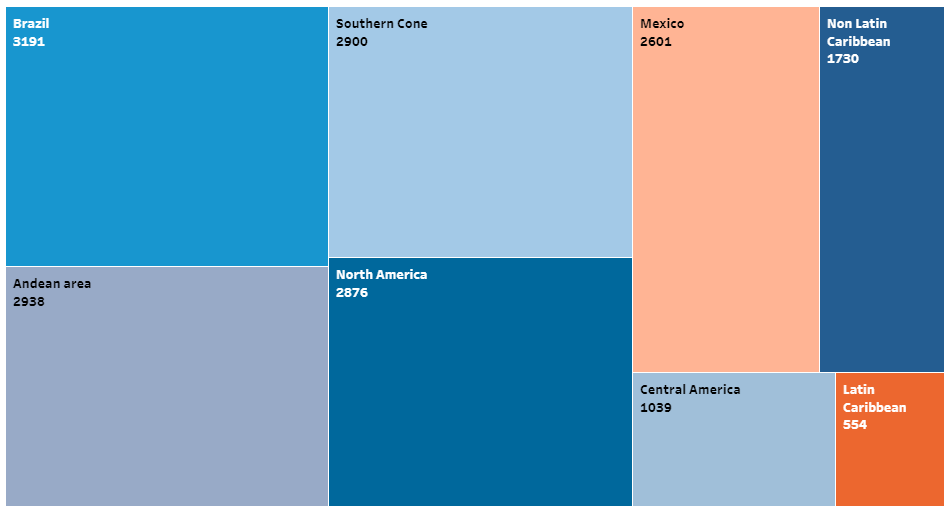

The Region of the Americas, with 13% of the world's population, has been one of the regions most affected by the pandemic, with 29% of confirmed cases and 44% of deaths, globally. As of 31 August 2022, there were 175 771 144 cases of COVID-19 in the Region (52%, women; 48%, men). North America recorded 55% of all cases in the Region of the Americas, but 62% of all deaths occurred in Latin America and the Caribbean (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.1. Confirmed COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 deaths in the Region of the Americas, by subregion and week of notification

This figure shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Region of the Americas from 1 January 2020 until 31 August 2022. Click the button options to view cases and deaths by week or cumulatively. The figure can be viewed in linear or log scale The yellow button allows you to view cases and deaths by subregions.

Figure 3.2. COVID-19 deaths per million population vs. cases per million population, in the context of income groups

Considering population size, burden of disease and mortality, and country wealth, this animated figure illustrates the changes in COVID-19 cases per million population for countries, since 1 January 2020 until the fully completed day the figure is viewed, graphed against cumulative deaths per million. The countries are shown according to World Bank income groups – high income (green), upper middle income (yellow), and lower middle income groups (red). Click on the “play” button at the left of the vertical (y) axis to see the change the number of cases and deaths by month. Note that you can individually select a country to illustrate the change over the period and view more information about each country.

Figure 3.3. Weekly confirmed COVID-19 deaths in the different WHO regions

This figure shows the number of COVID-19 deaths by the six WHO Regions. The first view shows the deaths for all six regions stacked. Click the "Comparison Chart" button on the left to view the deaths for each region, separately.

Figure 4. COVID-19 cases reported in the Region of the Americas, by subregion (number and percentage), as of 31 August 2022

Source: Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 trends. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://shiny.pahobra.org/wdc/.

Figure 5. COVID-19 deaths reported in the Region of the Americas, by subregion (number and percentage), as of 31 August 2022

Source: Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 trends. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://shiny.pahobra.org/wdc/.

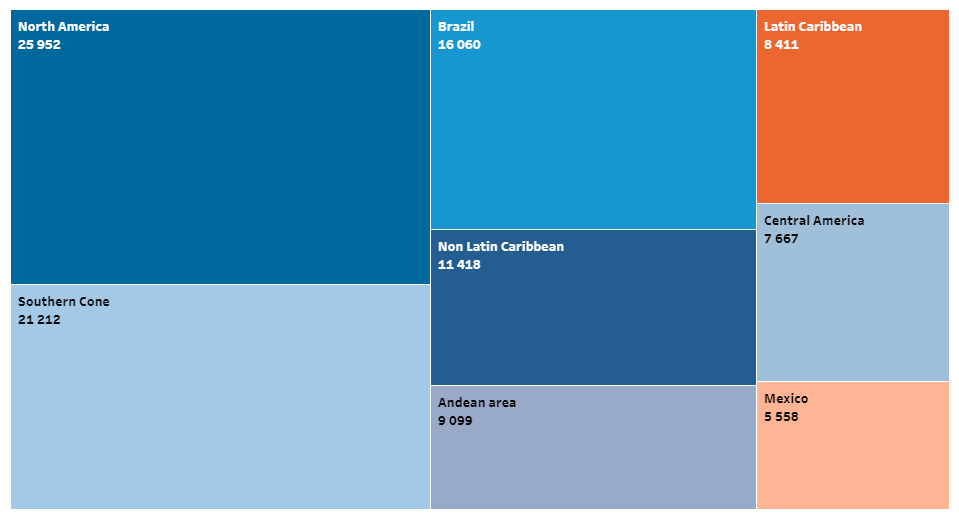

The North American subregion has reported the highest number of cases per 100 000 population throughout the pandemic (25 951.50 cases per 100 000 population), followed by the Southern Cone (21 212.17) and the non-Latin Caribbean (11 418.30) (Figure 6). This result possibly reflects better management of the information generated and more timely surveillance, detection, and diagnostic systems.

Figure 6. COVID-19 case rate per 100 000 population in the Region of the Americas, by subregion

Source: Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 trends. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://shiny.pahobra.org/wdc/.

The North American subregion also accounted for the highest proportion of deaths reported during the pandemic (Figure 7), with a total of 1 079 383 cumulative deaths reported as of 31 August 2022. However, when comparing the cumulative mortality rate per million population, the highest rate was recorded in Brazil (3191), followed by the Andean zone (2938) and the Southern Cone (2900).

Figure 7. COVID-19 mortality rate in the Region of the Americas, by subregion, per million population

Source: Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 trends. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://shiny.pahobra.org/wdc/.

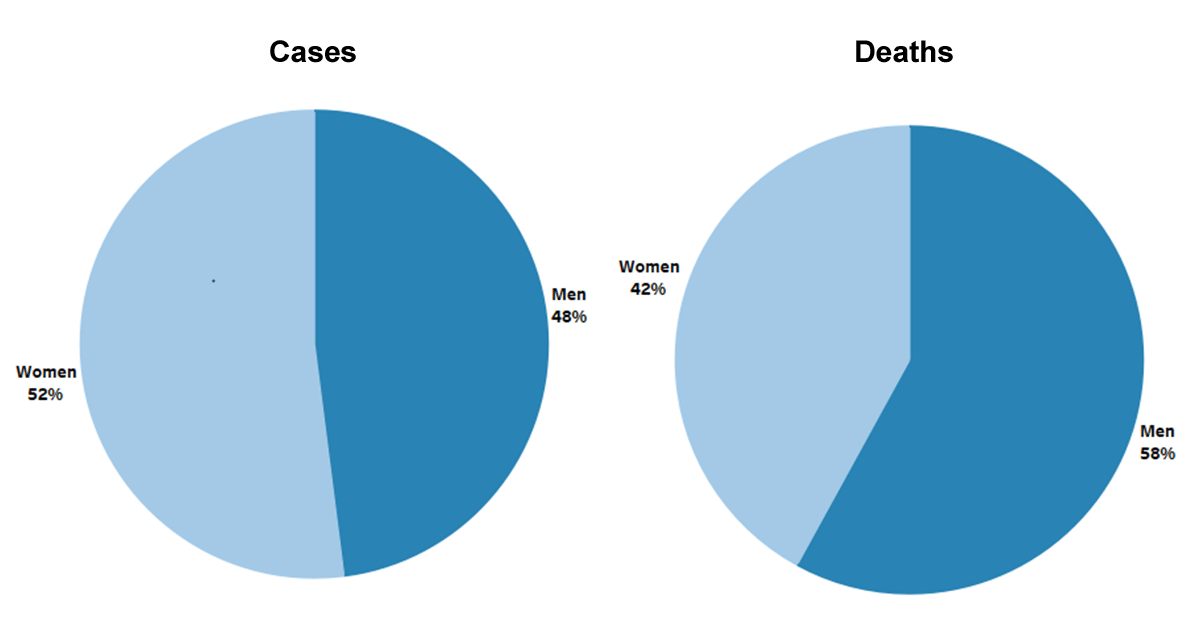

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), global data disaggregated by sex show that the number of confirmed cases is higher for women than for men (Figure 8). However, the opposite is true for deaths: men represent 58% of total deaths, compared to 42% for women (,).

Figure 8. Distribution of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Region of the Americas, by sex (%)

Source: WHO COVID Surveillance Detailed Dashboard, 2022. Available from: https://app.powerbi.com.

Source: WHO COVID Surveillance Detailed Dashboard, 2022. Available from: https://app.powerbi.com.

According to the recent WHO report on excess deaths due to COVID-19, it is estimated that there were 3.23 million deaths in the Region of the Americas, or 430,000 more deaths than were reported (). Five countries (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and the United States of America) accounted for 83.5% of excess mortality. Due to its high mortality rate, COVID-19 was among the leading causes of death in 2020 and 2021.

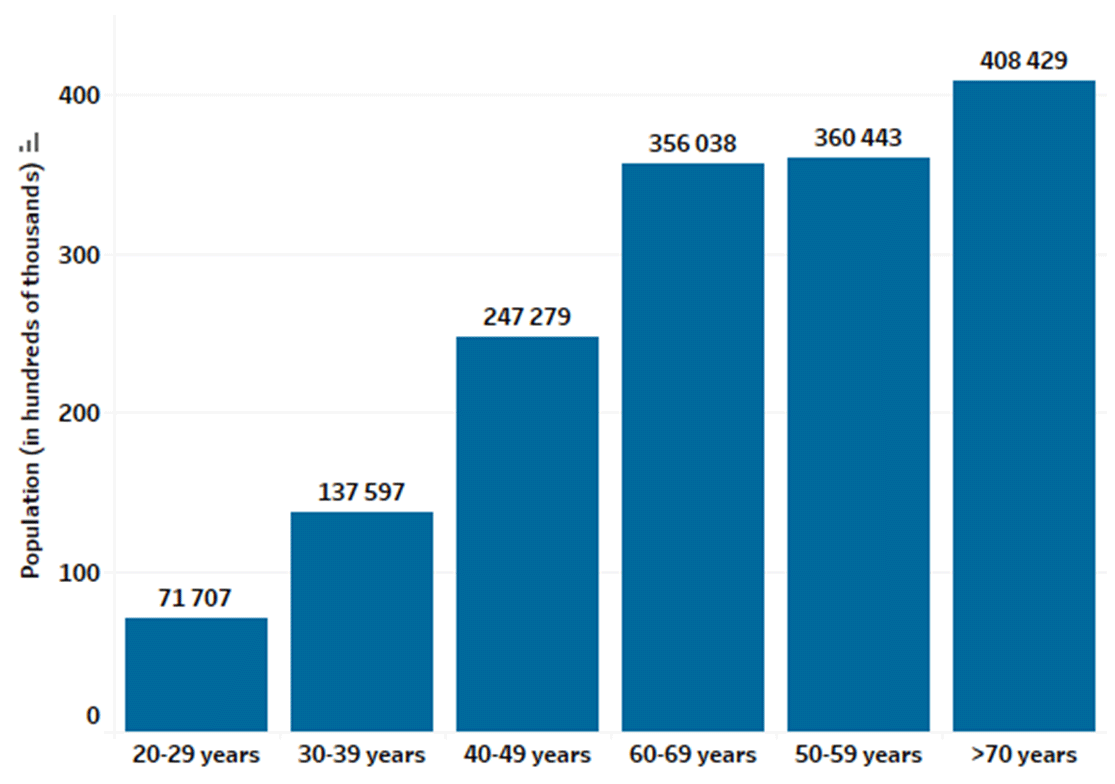

Globally available data disaggregated by age groups show that total cases are disproportionately concentrated in the population aged 20 to 50 years. In the Americas, it is estimated that the population over 70 accounts for 9.1% of cumulative cases, with 51% of cumulative deaths in this age group, as shown in Figure 9. Likewise, in the countries of the Region of the Americas, COVID-19 mortality increases exponentially with age. Vaccination has certainly reduced the risk of death overall, although the risk remains higher among older adults.

Figure 9. Proportional distribution of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the Americas by 5-year age groups for 2020, 2021, and 2022

There are two different options to view the information. The first view shows the age-adjusted rate of COVID-19 cases and deaths per million population group.

The second option presents the data in a chart.

Regarding socioeconomic inequalities, studies in several countries of the Region have documented higher COVID-19 mortality in populations in conditions of vulnerability, including people residing in areas with higher concentrations of poverty and indigenous populations.

Life expectancy in the Region

Life expectancy in Latin America and the Caribbean decreased from 75.1 years in 2019 to 72.2 in 2021 (2.9 years less); and in North America it decreased from 79.5 years in 2019 to 77.7 in 2021 (1.8 years less) (), . This was mainly due to the impact of COVID-19, with the greatest loss of life expectancy in Latin America and the Caribbean. Life expectancy in 2021 for Latin America and the Caribbean and for North America is comparable to the figure for 2004. During this period, in both Latin America and the Caribbean and in North America, life expectancy decreased more for men than for women (Table 1)

Table 1. Life expectancy in the Region of the Americas, by subregion and sex, 2004, 2019, and 2021, in years

| Subregion | Life expectancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2019 | 2021 | Years lost between 2019 and 2021 | |

| North America | 77,8 | 79,5 | 77,7 | 1,8 |

| Men | 75,2 | 76,9 | 74,9 | 2,0 |

| Women | 80,3 | 81,9 | 80,7 | 1,2 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 72,3 | 75,1 | 72,2 | 2,9 |

| Men | 69,5 | 71,9 | 68,8 | 3,1 |

| Women | 75,9 | 78,3 | 75,8 | 2,5 |

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022. New York: United Nations; 2022. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/

Health Systems and Services

With exceptions, health systems in the Americas have been characterized by underfunding, segmentation, and fragmentation. Despite ongoing processes to reform and strengthen the health sector in the countries of the Region, the progress made has failed to protect countries from the pressures of the pandemic. Public expenditure on health is low, averaging 3.8% of gross domestic product, far from the established target of 6%. This is reflected in deficits in infrastructure and human resources available for health.

The level of out-of-pocket expenditure on health in the Region is high, increasing the risk of impoverishing households. It is also one of the main sources of inequity in access to health services, because it implies a lack of financial protection for people who are in situations of greatest vulnerability and who are most exposed to catastrophic expenses in case of illness.

The enormous pressure of the pandemic on health systems in the countries of the Region has exposed, once again, the long-standing gaps in universal health that exacerbate inequalities in access to effective and comprehensive health services (,). Health services have faced unprecedented increases in demand in a scenario of limited available resources to address a new and severe situation that quickly escalated into a global public health, social, and economic crisis.

The pandemic also highlighted the challenges faced by health systems in ensuring universal access to health and universal health coverage. Adapting and retrofitting services to increase care capacity allowed for greater attention to people with the new disease, but also weakened the delivery of other services, particularly in peri-urban, rural, and indigenous areas.

Strengthening of the first level of care was uneven across countries. One of the most important actions recommended as part of the COVID-19 response in the health service delivery area was to reorganize and strengthen the capacity of the first level of care to participate in containing the spread of the disease, early detection of SARS-CoV-2, initial case monitoring and treatment , and prioritization of services in all areas, while maintaining essential services ().

The degree of effectiveness of these actions depended largely on pre-existing public health capacities in the countries. In many cases, capacity gaps limited a comprehensive and integrated response, leading to delayed response measures, disruptions in the continuity of essential services, exacerbation of access barriers, and low COVID-19 vaccination rates. By May 2020, nearly 20 countries had incorporated primary care services into the COVID-19 response, although they were not operating at full capacity. Mental health, communicable diseases, and sexual, reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child, and adolescent health services were the most affected (Table 2).

Table 2. Countries in the Region of the Americas with disruptions in health services, by area of care (%)

| Health service area | Countries with service disruptions (%) |

|---|---|

| First level of care | 70 |

| Vaccination | 69 |

| Care for older people | 67 |

| Nutrition | 64 |

| Neglected tropical diseases | 53 |

| Mental health, neurological, and substance use disorders | 47 |

| Communicable diseases | 38 |

| Sexual, reproductive, maternal, neonatal, infant, child, and adolescent health | 32 |

Source: Pan American Health Organization. Third round of the National Survey on the Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: November-December 2021. Interim report for the Region of the Americas, January 2022. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56128.

By the end of 2021, 93% of countries reported disruptions in the provision of essential health services in all modalities, with 26% reporting 75-100% disruptions in services, and 55% reporting average disruptions in the 66 services analyzed; 70% of countries reported disruptions in primary care, palliative care, and rehabilitation services.

Reductions were observed in all services, which have been reflected in declines in health indicators. For example, there has been a widely unmet need for modern contraceptive methods in the Region (14.5-17.7%), resulting in an estimated 1.7 million unplanned pregnancies, nearly 800 000 abortions, 2900 maternal deaths, and nearly 39 000 infant deaths, representing a setback equivalent to 20-30 years of progress in this field ().

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the average number of hospital beds in Latin America and the Caribbean was 2.1 per 1000 population in 2020, less than half the average figure for OECD countries (4.7) (). In addition, the biggest bottleneck for the treatment of severe COVID-19 was the limited capacity of intensive care beds due to high occupancy rates, which in many countries of the Region exceeded 70%, becoming an emergency in itself (). As a result, one of the first actions health services took in order to provide care to COVID-19 patients was to retrofit hospital beds for patients with severe infection, supported by emergency medical teams, establish mobile hospitals and alternative sites, and provide oxygen in hospitals, first-level care centers, and homes.

An analysis of information from ministries of health official communication sites conducted in 16 countries between March 2020 and September 2021 shows that the number of intensive care beds went from 61 406 to 122 501, for a 99% increase in installed capacity (61 095 new beds). In other words, the services doubled the number of beds in just 18 months.

Human resources for health

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic has once again highlighted the chronic deficit and poor distribution of human resources for health in the Region. There is also evidence of a lack of policies, strategic planning processes, and investment in the development of a fit-for-purpose health workforce in many countries.

Globally, the majority of health workers are women (nearly seven out of 10). In the Region, 56% of human resources for health are nursing staff, 89% of them women. In addition to their work responsibilities, women are also the primary family caregivers and, in many cases, the main breadwinners. Expectations of women have increased significantly during the pandemic, which has caused them added stress and affected their mental health and well-being. Studies among health personnel in the Region show high levels of mental disorders in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States.

To ensure the functioning of the health system, changes have been required in strategic planning and regulation for health personnel, and in support and capacity-building for these workers. Many countries have also faced pre-existing health workforce challenges, including shortages (estimated at 15 million workers globally in 2020, and 10 million by 2030, mainly in low- and lower-middle-income countries), poor distribution, and misalignment with respect to needs and skills.

In the period between the confirmation of the first cases of COVID-19 in the Americas and 29 November 2021, at least 2 397 174 cases have been reported among health personnel, including 13 081 deaths, according to information available from 41 countries and territories of the Americas (Table 3) (). The cases represent 16% of all health personnel, estimated at 15 million in the Region (). Moreover, recent WHO-led studies have estimated more than 115 000 COVID-19 deaths among health workers globally (including some 60 000 in the Americas) ().

Table 3. Number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and cumulative deaths among health personnel in the Region of the Americas, by country and territory, January 2020 to 30 November 2021

| Country/Territory | Confirmed cases of COVID-19 | Deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Anguilla | 13 | 0 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 44 | 2 |

| Argentina | 240 261 | 1273 |

| Aruba | 301 | 0 |

| Bahamasa | 955 | 14 |

| Belize | 542 | 4 |

| Bermuda | 59 | 0 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of)a | 28 418 | 456 |

| Bonaire | 123 | 1 |

| Brazil | 655 105 | 903 |

| Canadaa | 113 105 | 64 |

| Chilea | 64 681 | 134 |

| Colombia | 68 230 | 337 |

| Costa Rica | 8969 | 57 |

| Curaçao | 138 | 0 |

| Dominicaa | 1 | 0 |

| Ecuador | 13 332 | 156 |

| El Salvadora | 7643 | 79 |

| United States | 761 378 | 2810 |

| Grenadaa | 14 | 0 |

| Guatemalaa | 8642 | 65 |

| Haitia | 781 | 3 |

| Hondurasa | 13 668 | 115 |

| Cayman Islands | 36 | 0 |

| Falkland Islandsa | 12 | 0 |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 110 | 0 |

| Virgin Island (British)a | 141 | 0 |

| Jamaicaa | 861 | 4 |

| Mexicob | 286 285 | 4572 |

| Panama | 9078 | 115 |

| Paraguay | 17 839 | 183 |

| Peru | 76 099 | 1475 |

| Dominican Republic | 1645 | 23 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevisa | 34 | 0 |

| Saint Eustatius | 8 | 0 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadinesa | 31 | 0 |

| Saint Lucia | 246 | 0 |

| Sint Maarten (Netherlands) | 73 | 0 |

| Suriname | 1722 | 3 |

| Uruguay | 9745 | 28 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)a | 6806 | 205 |

| Total | 2 397 174 | 13 081 |

Notes: a Latest available data is from 30 October 2021.

b The information corresponds to the 'occupation' variable of the Epidemiological Surveillance System for Viral Respiratory Disease (SIS VER). The analysis reflects the cases reported as performing a health-related occupation. The information collected in SIS VER does not make it possible to identify whether infection occurred in the workplace, at home, or in the community; nor does it indicate whether health workers are currently part of a medical care unit.

Source: Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological Update: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) -: 2 December 2021. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2021. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-update-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-2-december-2021.

The countries of the Region developed various strategies aimed at optimizing the availability of human resources while guaranteeing their safety and working conditions, including the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) and instructions for its use, safety guidelines for staff, economic incentives for those working in direct care of COVID-19 patients, recognition of COVID-19 as an occupational disease, life insurance coverage for staff, and interventions to address their mental health issues.

Routine immunization program

Over the past decade, routine childhood vaccination programs have significantly contributed to reducing vaccine-preventable diseases and saving millions of lives. Despite the progress made, the impact of the pandemic was also associated with disruptions to vaccination activities.

Administered doses as well as subsequent vaccination coverage have declined in the Region since 2020 (Table 4). The subregions that have experienced significant reductions in supplied doses are North America, followed by the Southern Cone and the Andean Area for DTP-1 (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis), DTP-3, and MMR-1 (measles, mumps, and rubella). Declines in coverage range from 3.7% for the DTP-3 vaccine to 10.3% for MMR-2 (Table 5). In this context, PAHO is working with countries and partners to improve vaccination coverage and reduce the risk of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in the effort to leave no one behind.

Table 4. Relative difference in doses of different vaccines administered in the Region of the Americas, by subregion, comparison between 2021 and 2019

| Subregion | DTP-1 (%) | DTP-3 (%) | MMR-1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | –51,2 | –38,5 | –50,4 |

| Brazil | –22,4 | –12,4 | –35,9 |

| Latin Caribbean | –9,5 | –10,5 | –11,6 |

| Non-Latin Caribbean | –12,8 | –12,7 | 12,8 |

| Central America | –24,8 | –24,6 | –24,8 |

| Southern Cone | –42,8 | –44,8 | –45,3 |

| Andean Area | –42,8 | –36,5 | –31,3 |

Source: Pan American Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on the coverage of the systematic vaccination program 2019-2021. Washington, DC: PAHO. Unpublished.

Table 5. Vaccination coverage in the Region of the Americas, 2019–2021

| Vaccine | 2019 (%) | 2020 (%) | 2021 (%) | Decrease (2019-2021*)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTP-1 | 89 | 88,6 | 86 | 3,5 |

| DTP-3 | 84 | 85 | 81 | 3,7 |

| PCV (last dose) | 86,8 | 81,7 | 80 | 8,5 |

| Polio3 | 87 | 82 | 79 | 9,8 |

| MMR-1 | 87 | 87 | 85 | 2,4 |

| MMR-2 | 75 | 65 | 68 | 10,3 |

Notes: a Estimate by the Pan American Health Organization.

DTP: diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis; PCV: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; Polio3: poliomyelitis. MMR: measles, mumps, and rubella.

Source: Pan American Health Organization. Immunization Reported Coverage. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://ais.paho.org/imm/IM_JRF_COVERAGE.asp.

Information systems and digital transformation

Having health information systems that are functional, interconnected, and interoperable has proven to be a strategic tool for decision-making related to the pandemic response. Developments and innovations in information systems and epidemiological surveillance have made it possible to anticipate the path of the pandemic using digital tools such as chatbots, platforms, and applications (for example, artificial intelligence, robotics, telehealth, blockchains, and the internet of things), as well as artificial intelligence to control the infodemic, processing and analysis of available data, and development of simulation models, among others.

Access to data, information, and multimedia content has been simplified thanks to the massive use of the internet, social networks, and mobile technologies. However, these same mechanisms generate an information overload that is very difficult to manage in rapid decision-making processes, while facilitating the circulation of false or distorted information; this is part of the infodemic that has led to a reluctance to be vaccinated, resistance to following preventive measures and, in many cases, incorrect self-medication or abandonment of treatment, among other effects.

At the same time, the incorporation of digital applications in the fields of health and public health has helped to improve patient monitoring (for COVID-19 and other conditions), management of medical health records, responsible self-care, teleconsultations, tele-education, automatic capture of critical data, and issuance of digital vaccination certificates and mobility passes, among others. All this has made it possible to maintain access to health services, reducing the cost of care and bringing health care closer to areas and populations in situations of vulnerability.

Also, the use of artificial intelligence has played a prominent role in the area of procurement during the pandemic and has been essential in more efficiently solving complex problems such as automating tasks, designing more effective distribution routes, automatically capturing new data sources, and above all, ensuring that the management of relationships with international suppliers is based to a greater extent on transparent and quality data. Nevertheless, significant digital gaps in connectivity and bandwidth for appropriate internet access persist in the Americas; if not addressed with timely public policies, these gaps could exacerbate existing inequities.

Communicable diseases and COVID-19

In the past ten years, several countries have reached milestones in the elimination of diseases such as malaria, rabies transmitted by dogs, onchocerciasis, foot-and-mouth disease, Chagas disease, and trachoma, as well as in mother-to-child transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis. However, the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it significant challenges. Factors that have hampered health program operations include the service disruptions due to quarantines and restrictions on the movement of people imposed by several countries; a lack of resources and critical supplies for patient care and the continuation of prevention and control services; reorientation and redistribution of human and financial resources to respond to the pandemic; and problems in international and domestic supply chains for medicines and other inputs.

Reversing progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets for tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria is a major setback on the road to achieving SDG 3 and closing inequality gaps in vulnerable populations. The Results Report 2021 of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria presents a devastating scenario with respect to achieving the targets for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria following COVID-19 (). The pandemic caused multiple disruptions in all established interventions for the management, control and elimination of communicable diseases, including their diagnosis and treatment (Table 6).

Table 6. Percentage of countries in the Region of the Americas that reported disruption of services and programs for the control and prevention of communicable diseases

| Disruptions | Countries (%) |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis | 65 |

| Access to diagnostic tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | 50 |

| Diagnosis and treatment of malaria | 50 |

| Diagnosis and treatment of viral hepatitis | 43 |

| Prevention services | 59 |

Source: Pan American Health Organization. Third round of the National Survey on the Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: November-December 2021. Interim report for the Region of the Americas, January 2022. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2022. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56128.

In addition, nearly half of the countries experienced disruptions in care services for neglected infectious diseases and other communicable diseases, including regular vector control activities, mass delivery of medicines, and screening of populations at risk of infection. Due to the reallocation of resources in response to the pandemic, it continues to be complicated to resume actions in various services, putting at risk the fulfillment of the commitments made to eliminate these diseases by 2030. In addition, health supply chains, which are essential in providing diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, suffered disruptions in 40% of countries.

The global antimicrobial resistance crisis has been aggravated by the emergence of new and more complex resistance mechanisms. This relates to the increased use of antimicrobials to treat COVID-19 patients, as well as gaps in infection prevention and control practices in overburdened health systems.

Addressing inequalities related to HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria is a complex issue that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. To respond to these challenges, it is necessary to strengthen people-centered primary health care, universal health, and multisectoral actions with a focus on the social determinants of health.

Human immunodeficiency virus

In 2020, most countries in the world did not reach the 90-90-90 targets of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The same year, based on UNAIDS Spectrum estimates, in Latin America and the Caribbean there was an 8.7% increase in the coverage of antiretroviral therapy, despite COVID-19.

Based on data reported by 20 countries to UNAIDS, in 2020 there was a 34% decrease in the number of people tested for HIV compared to 2019, and a 27% decrease in the number of people with a new positive HIV diagnosis. The reduction in the number of people tested and diagnosed as HIV-positive did not fully reverse in 2021. It is also important to note that in 2020 there were 34 526 people on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) compared to 19 783 in 2019 (32, 33). (,).

Tuberculosis

COVID-19 has replaced tuberculosis as the world's leading deadly infectious disease; however, tuberculosis remains a leading infectious disease, second only to COVID-19. In the Americas, estimated TB deaths increased from 24 000 in 2019 to 27 000 in 2020, a trend that is projected to continue in 2021 and 2022.

In 2020 there was a 17% increase in people diagnosed with tuberculosis, compared to 2019. In the same period, there was a 19% reduction in people in treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis, along with a 20% decrease in HIV/TB patients on antiretroviral therapy during tuberculosis treatment. Also, there was a 27% decrease in the child population under 5 years of age in contact with tuberculosis patients who received preventive therapy ().

Malaria

COVID-19 has been associated with a reduction in the total number of malaria cases at the regional level. The results were uneven within countries, with sharp reductions in some countries and increases in others. The pandemic had a general impact on malaria surveillance, with a decrease in case detection, active surveillance, and deployment and coverage of vector control actions.

In the 2019-2020 period, the number of mosquito nets distributed to protect families from malaria decreased by 20.6%. In the same period, there was a 28% reduction in the number of people tested for malaria, and a 46% reduction in the population protected with indoor residual spraying (,).

Noncommunicable diseases and COVID-19

Comorbidity

Before the pandemic, noncommunicable diseases accounted for 81% of deaths in the Americas, led by cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and Alzheimer's disease, and other dementias. In the Region, 24% of people had at least one underlying condition, although this value varies by subregion: Latin America accounts for 22% and the non-Latin Caribbean for 29% (). This pattern coincides with the comorbidities presented by persons with COVID-19 and is associated with a greater risk of serious illness ().

Different analyses have shown an increased risk of death from COVID-19 in people with pre-existing noncommunicable diseases, particularly diabetes, hypertension, and obesity (). Of the total reported cases of COVID-19, 1 509 786 had at least one comorbidity. The number of cases with at least one comorbidity increases with age, and the over-70 age group accounted for 28% of reported cases (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Number of patients with at least one reported comorbidity in the Region of the Americas, by age group, from 1 January 2019 to 8 September 2022

Source: Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 Data reported by countries and territories in the Region of the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO, 2022. Available from: https://ais.paho.org/phip/viz/COVID-19EpiDashboard.asp.

As for COVID-19 patients admitted to an intensive care unit or who required ventilatory support, there is only one example ( not necessarily representative) in which 24.6% and 23.4% of total cases, respectively, had at least one reported comorbidity. Of the 371 789 patients admitted to an intensive care unit, cardiovascular disease was recorded in 60% of cases (182 846), followed by diabetes in 30% of cases (90 902). Of the 352 537 patients on a ventilator, 50% (177 556) reported cardiovascular disease, followed by diabetes in 23% of cases (80 727).

Mental health

The magnitude of mental health disorders in the population during the COVID-19 pandemic has not yet been fully documented. However it is clear that interpersonal relationships, in particular, have been negatively affected, with increases in reported cases of domestic violence and in calls for help to mental health services.

The different mitigation measures implemented in the countries to control the spread of the pandemic (quarantines, restrictions on mobility, and physical distancing) increased anxiety, depression, and consumption of addictive substances in large sectors of the population (,). Anxiety associated with the pandemic has led to the description of a COVID-19-related stress syndrome (). Canada and the United States have reported that 38% of adults experienced some degree of distress, and 16% experienced elevated levels of anxiety, further burdening the demand for mental health services ().

The prevalence of depression and anxiety due to the COVID-19 pandemic increased until January 2021, if analyzed in terms of both reported daily SARS-CoV-2 infections and changes in mobility. These conditions were observed particularly in young people, women, people in situations of socioeconomic vulnerability, and people with pre-existing mental disorders (). These increases represent 53.2 million additional cases of major depression and 76.2 million additional cases of anxiety disorders—increases of 27.6% and 25.7%, respectively, compared to pre-pandemic levels ().

Studies have shown that the pandemic has amplified risk factors associated with suicide, such as loss of employment and financial loss, trauma and abuse, mental health disorders, and barriers to accessing health care. A study in the Region by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) indicates that 27% of adolescents and young people reported symptoms of anxiety and 15% reported symptoms of depression, while a third of them identified the economic situation as the main trigger of these states (). Furthermore, 43% of women and 31% of men said they felt pessimistic about the future (). Among health personnel, studies in the Region show high levels of mental disorders in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States.

Mental health should be permanently positioned on the same level as physical health. Countries should guarantee access to mental health services, prioritize vulnerable populations, and develop strategies and initiatives in conjunction with the education and labor sectors for early identification of mental health conditions that require care.

Pregnancy

A comparative study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that pregnant women are 5.4 times more likely to be hospitalized than non-pregnant women of the same ethnicity and age. Their risk of being hospitalized in an intensive care unit is also higher, and the risk of needing mechanical ventilation is 1.7 times higher ().

While the overall risk of severe illness and death for pregnant people remained low globally, the effects of the pandemic on this population group in the Region of the Americas were especially severe. According to data from 24 countries in 2021, there was an increase in both the number of cases and deaths among SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people compared to 2020 (Table 7). Most countries reported a higher maternal mortality ratio in 2021.

Table 7. Selected indicators for COVID-19 in pregnant people, Region of the Americas, 2020 and January-November 2021

| Country | Number of SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people | Number of deaths in SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people | MMRb (per 100 000 live births) | Number of SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people | Number of deaths in SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people | MMRb (per 100 000 live births) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 (January to November) | |||||

| Argentina | 9001 | 41 | 5,5 | 13 483 | 174 | 23,2 |

| Belize | 181 | 2 | 28,4 | 445 | 8 | 150,6 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 963 | 31 | 12,5 | 2442 | 20 | 8,1 |

| Brazil | 5489 | 256 | 9 | 9871 | 1046 | 37 |

| Canada | 2925 | 1 | 0,3 | 5627 | 2 | 0,5 |

| Chile | 6610 | 2 | 0,9 | 9220 | 14 | 6,2 |

| Colombia | 7994 | 56 | 7,7 | 10 765 | 137 | 22,4 |

| Costa Rica | 335 | 3 | 0,4 | 1048 | 9 | 0,1 |

| Cuba | 180 | 0 | 0 | 5769 | 95 | 87,3 |

| Ecuador | 1589 | 29 | 8,6 | 1255 | 28 | 8,3 |

| El Salvador | 272 | 10 | 9 | 292 | 5 | 4,5 |

| United States | 68 459 | 80 | 2 | 79 057 | 160 | 4 |

| Guatemala | 652 | 8 | 1,9 | 1306 | 7 | 1,6 |

| Haiti | 79 | 4 | 5,1 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Honduras | 508 | 15 | 7,2 | 310 | 41 | 19,6 |

| Mexicoa | 10 568 | 205 | 9,4 | 20 293 | 431 | 25,5 |

| Panamaa | 1697 | 9 | 11,3 | 922 | 5 | 6,3 |

| Paraguaya | 599 | 1 | 0,7 | 1563 | 88 | 61,5 |

| Peru | 40 818 | 81 | 14,3 | 14 622 | 109 | 19,2 |

| Dominican Republic | 707 | 36 | 21,7 | 879 | 9 | 6,3 |

| Saint Lucia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Surinamea | 184 | 2 | 18,9 | 396 | 20 | 189,8 |

| Uruguay | 106 | 0 | 0 | 1659 | 12 | 25,5 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 338 | 9 | 1.5 | 439 | 7 | 1,1 |

Notas: a Includes pregnant and postpartum people.

MMR: Maternal mortality ratio based on deaths of SARS-CoV-2-positive pregnant people (and in some cases, postpartum people) per 100 000 live births. The number of newborns is obtained from estimates provided at the PAHO Core Indicators Portal. See: Pan American Health Organization. Core Indicators Portal. Core Indicators Dashboard. Washington, DC: PAHO; [c2021]. Available from: https://opendata.paho.org/en/core-indicators/core-indicators-dashboard.

Source: Data provided by national focal points for the International Health Regulations or published by ministries of health, health institutes, or other similar health entities.