Leading the Way to Disease Elimination

Chapter 1: Overview of the Elimination Initiative

Summary

The Elimination Initiative is a comprehensive framework aimed at eliminating more than 30 communicable diseases and related conditions in the Americas by 2030. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has deep roots in disease elimination, and the initiative builds on more than 120 years of public health efforts. Taking an integrated, multisectoral approach to address the complex patterns of disease transmission, the Elimination Initiative focuses on four key areas: (1) strengthening health systems and service delivery integration, (2) improving health surveillance and information systems, (3) addressing social and environmental determinants of health, and (4) enhancing governance and financing. The initiative emphasizes equity, targeting populations living in vulnerable conditions and considering the entire life course in its approach.

Mere months after the Elimination Initiative launched, the COVID-19 pandemic began and slowed the initiative’s efforts. Even though progress has resumed post-pandemic, a number of other barriers still threaten to slow the progress of disease elimination efforts, including migration, the rise of noncommunicable diseases, health inequities, climate change, and resource constraints. Despite these obstacles, opportunities exist in the form of improved technology, increased awareness of social determinants of health, and innovations in service delivery accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Elimination Initiative provides a structured framework for countries to leverage these opportunities and address their specific contexts and priorities in the fight against communicable diseases.

Why the Elimination Initiative, and why now?

In the 2010s, the Region of the Americas was at a crossroads when it came to communicable disease elimination. While PAHO and its member states saw great success confronting certain diseases – particularly vaccine- preventable diseases like rubella and measles – new issues were emerging or becoming even more urgent. And despite progress improving health systems, developing new technologies, and strengthening multisectoral partnerships, there were more setbacks and challenges than ever. Climate change, vaccine hesitancy, inequalities accessing healthcare services, and new infectious diseases were just a few of the critical areas the Region was facing by the end of the 2010s. Clearly, the status quo disease elimination efforts were insufficient to tackle the complex patterns of disease transmission that continued to burden the Region.

While some programs tackled multiple diseases together, many diseases were still addressed in silos. PAHO and Member States recognized the need for a more ambitious, overarching framework to integrate services on a broader scale. Within this context, PAHO – under the leadership of Former Director Carissa Etienne – enacted a bold new initiative, one that brought structure and pragmatism to the complex problem of communicable disease elimination. It leveraged the structures that existed–systems, technology, integrated programs, and broad coalitions of stakeholders – and added a comprehensive framework that tied systems together to tackle more than 30 diseases and conditions under one umbrella framework. It also brought a community- and person- centered approach to the fore, ensuring that Member States leave no one behind in their efforts to conquer communicable diseases throughout the Region.

How the Elimination Initiative was established

Key convenings – including a 2015 Regional Consultation on Disease Elimination in the Americas – helped make the case and build momentum for multi-disease elimination efforts. With PAHO’s leadership, regional experts then developed the blueprint for what would become the Elimination Initiative. Unlike previous programs, this initiative was designed to not only combine diseases with similar modes of transmission (for example, syphilis and HIV), but to address broad categories of diseases and conditions responsible for the greatest disease burdens in the Region.

Ultimately, PAHO and Member States included more than 30 diseases and conditions in the Elimination Initiative, which was approved by PAHO’s Directing Council in September 2019. The ratification of the initiative aligned with PAHO Member States’ commitments towards related development and health policies, including the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (which created the Sustainable Development Goals) and the Sustainable Health Agenda for the Americas 2018–2030. 1, 2).

© PAHO

© PAHO

In March 2020 – just six months after the launch of the Elimination Initiative – the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global emergency. The pandemic’s sudden escalation caused severe disruptions to daily life, overwhelmed healthcare systems in many countries (reducing the access and availability of non-COVID-19 health services), interrupted supply chains, and triggered an economic crisis as businesses closed and unemployment soared. With high case numbers and death tolls across the Americas, COVID-19 also exposed and exacerbated existing inequalities.

While COVID-19 highlighted gaps in healthcare systems, it also presented new opportunities to deliver more comprehensive services. With this in mind, current PAHO Director Jarbas Barbosa da Silva Jr. ratified and re-launched the Elimination Initiative in 2023. This re-focus on the Elimination Initiative became a critical opportunity to encourage Member States, not only to strengthen systems to better confront the issue of communicable disease elimination but also to recover from the setbacks caused during the pandemic. In the wake of the pandemic, integrated, multi-disease elimination efforts can ultimately help countries resume and accelerate progress towards universal health.

While COVID-19 highlighted gaps in healthcare systems, it also presented new opportunities to deliver more comprehensive services. With this in mind, current PAHO Director Jarbas Barbosa da Silva Jr. ratified and re-launched the Elimination Initiative in 2023. This re-focus on the Elimination Initiative became a critical opportunity to encourage Member States, not only to strengthen systems to better confront the issue of communicable disease elimination but also to recover from the setbacks caused during the pandemic. In the wake of the pandemic, integrated, multi-disease elimination efforts can ultimately help countries resume and accelerate progress towards universal health.

Box 1. What is an “Integrated Approach” to disease elimination?

The term “integrated approach” is used throughout this report. In practical terms, this means approaching multiple health areas and services together to maximize health outcomes. The World Health Organization defines integrated health services as those that are “managed and delivered so that people receive a continuum of health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, disease-management, rehabilitation and palliative care services, coordinated across the different levels and sites of care within and beyond the health sector, and according to their needs throughout the life course.”a

Integrated approaches can manifest in various ways and can include combining delivery of services under one roof, promoting referrals and linkages among providers, combining monitoring and surveillance efforts, and promoting multi-sectoral policies focused on people’s needs in the context in which they live.

Below are some examples of integrated approaches related to disease elimination:

- Defining the contents and prioritizing the “single-visit” screen-and-treat approach for primary health care, and strengthening referral systems;

- Combining monitoring and surveillance for different diseases and health topics;

- Leveraging interventions in maternity hospitals to vaccinate or screen newborns and/or screen and treat pregnant women and newborns for mother-to-child transmitted diseases;

- Training staff at sexual and reproductive health clinics to screen, treat, and prevent HIV, syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), hepatitis B and C, human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers, and tuberculosis;

- Integrating water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) into housing initiatives to improve living conditions that impact multiple diseases;

- Using cost-effective integrated vector management approaches to control vector-borne diseases;

- Considering the impact of chronic communicable disease management within the elimination of communicable diseases;

- Recognizing the connections among the health of people, animals, and our shared environment by using the One Health approach;

- Deploying mobile health clinics and medical teams to address transportation issues that may prevent individuals from reaching health centers;

- Incorporate traditional healing practices into health systems to recognize and address intercultural issues.

a World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services: report by the Secretariat [Document A69/39]. Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly. Geneva: WHO; 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-sp.pdf.

Why is an “integrated approach” important to disease elimination?

The Elimination Initiative framework involves mobilizing the entire health system so that health programs and services are not carried out in silos. The Elimination Initiative approach also considers the specific needs of each setting and population, while contextualizing cross- border and regional issues that impact health programs and disease elimination efforts. Finally, one of the most important reasons to use an integrated approach is to ensure more community- and person-centered care – focusing not on the diseases themselves but the people and communities most affected by them.

The number and scope of communicable diseases and related conditions in the Americas is vast. Therefore, the Elimination Initiative includes selected diseases that represent a significant burden and disproportionally affect communities living in vulnerable situations: among them, Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons; and migrants. When developing the policy, PAHO also prioritized diseases that can readily be combatted using existing tools and technologies.

The Elimination Initiative recognizes and promotes linkages and synergies within the health system – as well as with other sectors. Multisectoral interventions are paramount for many of the diseases in the initiative. For successful implementation of this integrated framework, a range of stakeholders must be involved, including multiple government sectors, sponsors, donors, and funders, civil society representatives and organizations, and the private sector.

Diseases and conditions designated in the Elimination Initiative

Table 1 lists the diseases and related conditions included in the Elimination Initiative as candidates for elimination by 2030.

Elimination of Disease

- Bacterial meningitis epidemics

- Cervical Cancer

- Chagas Disease

- Cholera

- Congenital Chagas

- Congenital Syphilis

- Cystic Echinococcosis/ Hydatidosis

- Fascioliasis

- Hepatitis B and C

- Hepatitis B, mother-to-child-transmission (HBV-MTCT)

- HIV, mother-to-child-transmission (HIV-MTCT)

- HIV/AIDS

- Human rabies transmitted by dogs

- Leprosy

- Lymphatic Filariasis

- Malaria

- Onchocerciasis

- Plague

- Schistosomiasis

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Soil-transmitted Helminthiasis

- Trachoma

- Tuberculosis

Elimination of Environmental Determinants of Health

- Open defecation

- Polluting biomass cooking fuels

Maintain Elimination

- Congenital Rubella

- Measles

- Neonatal tetanus

- Poliomyelitis

- Rubella

- Yellow Fever Epidemics

Eradication

- Foot-and-mouth disease

- Yaws

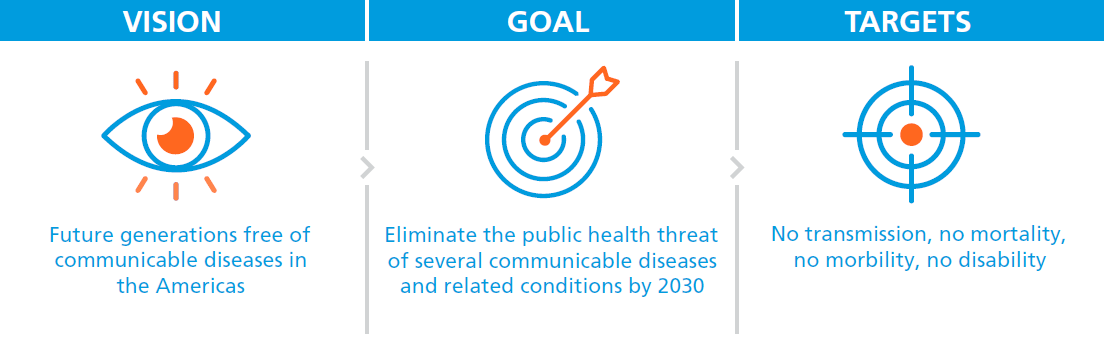

Figure 1. A renewed effort to accelerate elimination

The concept of elimination involves many techniques and modalities, depending on the disease in question. Box 2 provides definitions of the different levels of disease elimination3.

Box 2. Definitions of different levels of disease elimination

Elimination as a public health problem

Elimination of transmission

Eradication

Extinction

is defined by the achievement of measurable global targets set by WHO in relation to a specific disease. When these are reached, continued actions are required to maintain the achievements of the targets or to advance toward elimination of transmission.

(also referred to as interruption of transmission) is the reduction to zero of the incidence of infection caused by a specific pathogen in a defined geographical area, with minimal risk of reintroduction, as a result of deliberate efforts.

is the permanent reduction to zero of a specific pathogen, as a result of deliberate efforts, with no more risk of reintroduction.

is the eradication of a specific pathogen so that it no longer exists in nature or the laboratory, which may occur with or without deliberate efforts.

A bold blueprint for elimination

The Elimination Initiative’s conceptual framework (see Figure 2) can be adapted and implemented by Member States. In addition to presenting the four lines of action (detailed below), it recognizes that disease elimination efforts often require interventions targeted to specific life course phases, for example: pregnancy, preschoolers, school-age children, adolescents, adult workers, or older adults.

The Elimination Initiative also prioritizes approaches from the perspectives of gender equality, human rights, and populations in situations of vulnerability, addressing social determinants of health as defined by WHO (“the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life”)4. The initiative focuses on groups experiencing a greater disease burden due to complex social, economic, and systemic factors, including women, Indigenous Ppeoples, Afro-descendants, rural communities, LGBT individuals, migrants, and prisoners. As countries progress toward disease elimination, the initiative works to understand and improve the underlying conditions that hinder efforts among these communities.

The Elimination Initiative also prioritizes approaches from the perspectives of gender equality, human rights, and populations in situations of vulnerability, addressing social determinants of health as defined by WHO (“the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life”)4. The initiative focuses on groups experiencing a greater disease burden due to complex social, economic, and systemic factors, including women, Indigenous Ppeoples, Afro-descendants, rural communities, LGBT individuals, migrants, and prisoners. As countries progress toward disease elimination, the initiative works to understand and improve the underlying conditions that hinder efforts among these communities.

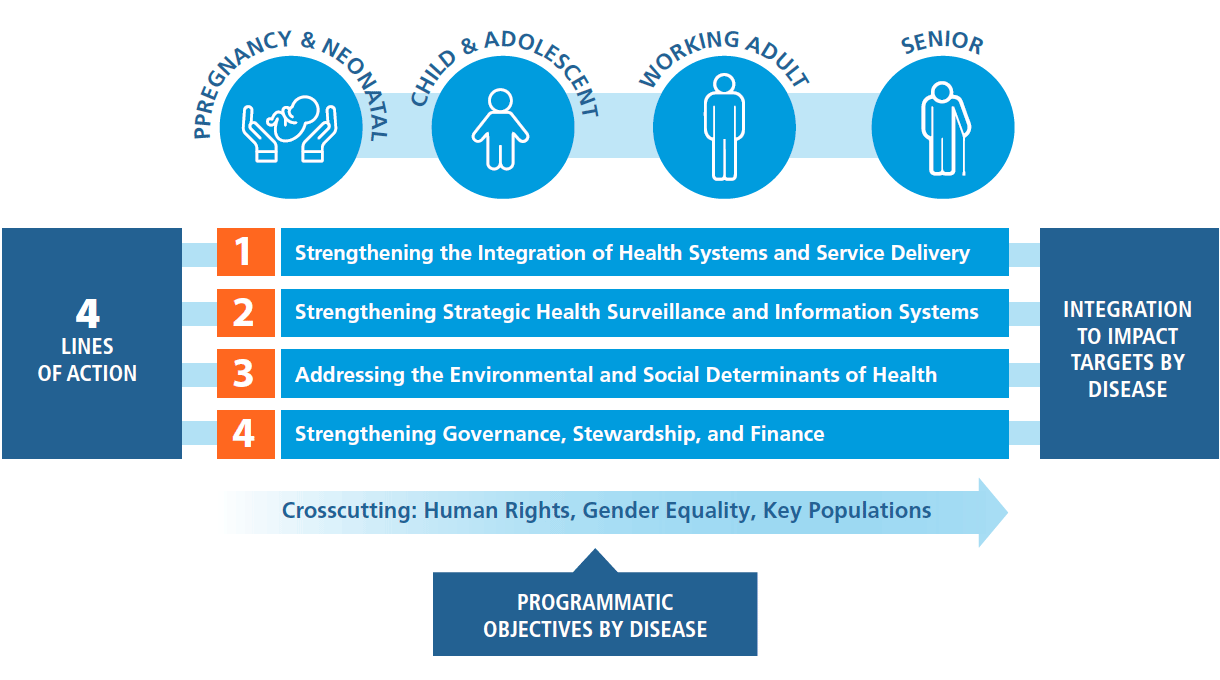

Figure 2. Conceptual framework: Line of action for integrated communicable disease elimination in the Americas through the life course

The four lines of action

Four lines of action were developed to guide the Elimination Initiative, strengthen countries’ capacities, and ensure that the initiative is sustainable. Each line of action is described below:

1 Strengthening the integration of health systems and service delivery

Vertical health programs, while effective for specific targets, can create barriers to comprehensive healthcare. The Elimination Initiative addresses this by combining multiple disease interventions into existing services and developing innovative approaches, focusing on strengthening primary healthcare at the community level. This comprehensive strategy improves service integration across various health areas, enhances demand for health services, and strengthens community–health service linkages, while ensuring access to essential medicines and health technologies. By promoting high-quality and integrated health services, this approach supports the achievement and maintenance of elimination targets for multiple diseases, improving overall health outcomes for individuals and communities.

2 Strengthening strategic health surveillance and information systems

Health information systems often operate in silos, with fragmented surveillance across sectors and limited communication between community, regional, and national levels. Integrating these systems can create efficiencies and synergies for addressing multiple diseases and conditions in the Elimination Initiative. This integration requires strengthening countries’ capacity to upgrade and unify surveillance systems, enabling more effective detection, assessment, monitoring, and reporting of health data across all relevant programmatic areas. Also, the interoperability of health information systems is vital for disease elimination; this helps support enhanced information flow for better decision-making, improved continuity of care, and cross-border collaboration necessary for effective regional disease elimination efforts.

3 Addressing the environmental and social determinants of health

Communicable diseases have a disproportionate impact on resource-constrained communities and other marginalized groups. Overall, the diseases in the Elimination Initiative are linked to diverse social determinants of health, including access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation, housing conditions, climate change risks, gender inequity, stigma and discrimination, sociocultural factors, and poverty, among others. Even evidence-based, cost-effective communicable disease interventions – for example, vaccines – are limited in their impact if health inequities related to social and environmental determinants are not addressed. People-centered interventions therefore require targeting the root causes of disparities. Addressing these mechanisms can help break the cycles of poverty (and other sources of inequity) while more effectively targeting the elimination of multiple diseases.

4 Strengthening governance, stewardship, and finance

To fully implement integrated health programming, it is essential to promote and normalize intersectoral collaboration-not only among different government institutions (for example health, education, and finance institutions) but nongovernmental sectors as well. To coordinate diverse partners, this process needs to involve dialogue with the private sector and civil society, as well as a range of government sectors. This will allow health authorities define clear roles and responsibilities to each actor engaged in the agenda to eliminate communicable diseases. In particular, strengthening the leadership of provincial/ departmental and municipal jurisdictions – as well as civil society through government arrangements – in the decision-making process is crucial to ensure that health initiatives and interventions are adapted to the community context.

Box 3. Examples of action in the Elimination Initiative

Strengthening the integration of health systems and service delivery:

- Build capacity of primary health care workers on a range of health topics, so they can detect and resolve multiple health issues (screening, diagnosis, and treatment) in a single visit;

- Strengthen laboratory and diagnostic services at the community level;

- Enhance planning, procurement, and supply of public health supplies – like vaccines and antivirals – for national programs.

Strengthening strategic health surveillance and information systems

- Undertake combined mapping of all diseases and conditions in the Elimination Initiative to better identify patterns, target resources effectively, and coordinate multi-disease strategies effectively;

- Conduct training and consultation for those managing health information and environmental monitoring systems;

- Provide periodic feedback to all stakeholders about advances in the elimination road map.

Addressing the environmental and social determinants of health

- Promote civil society participation in governance and local participatory planning and mapping, for determining the key pathways to elimination of communicable diseases;

- Foster multicultural approaches as part of community empowerment;

- Improve intersectoral collaboration to address a range of issues, from basic water and sanitation access to solid waste management to housing improvement and more.

Strengthening governance, stewardship, and finance

- Strengthen trust and partnerships with municipal governments and civil society toward Elimination Initiative targets;

- Mobilize local, subregional, and regional resources to ensure sustainability for communicable disease efforts;

- Improve financial commitments to increase access to cost-effective and innovative health technologies.

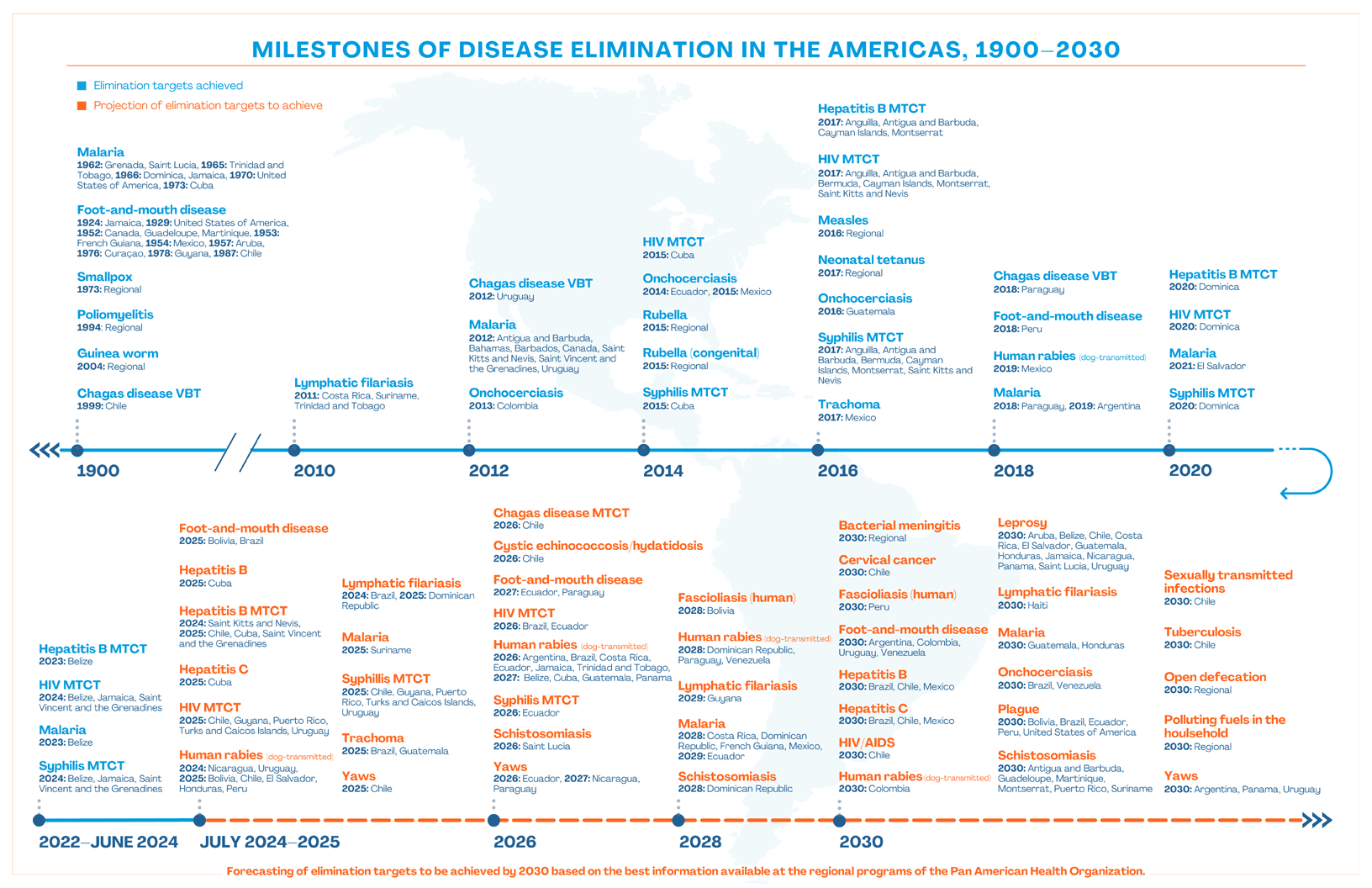

Landmark regional milestones and accomplishments: 1902 to present

Box 4. PAHO has deep roots in disease elimination

In 1870, a yellow fever epidemic struck Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay and within eight years had reached the United States, where it killed more than 20 000 people. Maritime transport, which was expanding rapidly along with international trade, was the main channel for the international spread of disease at the end of the nineteenth century. This need to protect people’s health and countries’ economies by controlling yellow fever transmission in the Rregion of the Americas led to the creation in December 1902 of what today is known as PAHO.

PAHO’s rich history tackling communicable diseases

Since PAHO’s founding in 1902, the Region has made significant progress toward disease elimination. Notable early achievements included substantial progress against yellow fever, particularly after the discovery of its mosquito-borne transmission in the early 1900s. Another early milestone was the Organization’s recognition of health as a right of all countries and all people through the Pan American Sanitary Code, ratified in 1924 and still in force today.

While rabies and smallpox vaccines had already been introduced to the Region in the nineteenth century, several additional vaccines were available by the middle of the twentieth century, including diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (available in the 1920s); yellow fever (1930s); influenza (1940s); and polio (1950s). Although availability and adoption varied widely, the Region started seeing dramatic reductions in some communicable diseases by the middle of the twentieth century. Other significant accomplishments during PAHO’s early decades included successful vector control campaigns starting in the 1940s. In 1946, a resolution was approved to eradicate the Aedes aegypti mosquito (a vector for yellow fever and other diseases) in the Region – it was eliminated from several countries by the 1960s. There were also major reductions in malaria prevalence, thanks largely to mosquito control efforts starting in the 1940s and the launch of an ambitious campaign in 1954. While not fully eliminated, control efforts also made considerable headway against Chagas disease through improved housing and insecticide use.

In the early 1950s, the concept of eradication of certain infectious diseases took hold in the Americas – particularly applied to malaria, yellow fever, and even tuberculosis. Additionally, campaigns against yaws in the 1950s and 1960s brought the disease close to elimination in many countries. In the 1960s, PAHO leaders began talking about the importance of integrating and strengthening health services, which had a great impact on the disease elimination campaigns that would follow.

Renewed efforts to accelerate disease elimination

Eventually, the Americas eliminated smallpox in 1973 (with eradication in 1980). In 1994, the Region was certified as free from poliomyelitis, after decades of working to control the epidemic. Over the last several decades, the Region continued to make progress towards eliminating malaria and several neglected infectious diseases including leprosy, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis (river blindness). Many countries also achieved substantial reductions in Chagas disease, soil- transmitted helminthiasis, schistosomiasis, and fascioliasis in children and other populations at risk. Additionally, one of the best global success stories of eliminating mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) comes from the Americas. In 2015, Cuba was validated by PAHO and WHO as the first country in the world to have eliminated MTCT of HIV and syphilis5. Also within the past decade, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and neonatal tetanus have also been eliminated from the Region.

Since its founding, PAHO’s technical support and convening power have been crucial in uniting diverse stakeholders around a common mission of disease elimination. However, these achievements resulted from collaborative efforts between PAHO and Member States, with strong commitments from governments, health workers, communities, partners, and donors. Based on over a century of sound scientific evidence, PAHO made a strong call to action and built on past achievements via the launch of the Elimination Initiative.

Box 5. Commitments leading up to the elimination initiative

The Elimination Initiative was by no means the first pledge to eliminate diseases in the Americas. Particularly in the last several decades, PAHO Member States approved dozens of resolutions to eliminate diseases, and some of them covered multiple diseases. The following are just a few examples of such resolutions and commitments in the Region:

- A 1990 PAHO resolution was passed to eliminate several diseases – including polio, measles, neonatal tetanus, rabies, and foot-and-mouth disease – by the year 2000;

- Beginning in 2000, PAHO and Member States’ efforts to meet the Millenium Development Goals were key to continued progress towards disease elimination;

- A 2009 PAHO resolution called for the elimination or control of 12 neglected diseases in the Americas by 2015;

- In 2010, PAHO Member States approved a resolution to eliminate the transmission of HIV from mother to child and congenital syphilis;

- In 2015, the Regional Consultation Disease Elimination in the Americas mobilized Member States around this issue and formed the blueprint of the Elimination Initiative;

- A 2016 plan of action called for the prevention, control, and reduction of disease burdens associated with neglected infectious diseases.

Due to these continued commitments – along with enormous efforts throughout the Region to increase vaccination rates, reinforce country capacities, strengthen health systems, and increase domestic funding – momentum for disease elimination efforts was building by 2019 when the Elimination Initiative launched. However, these resolutions only offered part of the solution and only included certain groups of diseases. The Elimination Initiative presented a bigger, bolder framework for multi-disease elimination on multiple fronts.

© PAHO

© PAHO

Approaches brought forward from earlier disease elimination efforts

Over time, PAHO and Member States have documented experiences and practical knowledge related to disease elimination – this serves as the foundation of the Elimination Initiative, including the lines of action. Some key learnings and approaches incorporated into the initiative are summarized below.

Benefits of integrated programs

Traditionally, disease elimination efforts concentrated on single diseases. While each disease does indeed need to be understood separately – looking at modes of transmission, effective treatment, vaccines, etc. – viewing each disease in a silo can be limiting. In looking at multiple diseases at the same time, Member States have identified common challenges related to policies, programs, and services. For example, vaccine-preventable diseases often share common risk factors, modes of transmission, supplies, and prevention measures. Health systems with a more integrated approach to manage disease programs, may be more effective to achieve common goals.

Over time, PAHO and its Member States grew to appreciate the need to find solutions and plan programs to fight multiple diseases together. In 2015 PAHO convened the Regional Consultation on Disease Elimination in the Americas to discuss advancing elimination efforts in the Region and bundle various mandates and strategies focusing on individual communicable diseases into an integrated package. The consultation highlighted numerous synergies and opportunities for collaboration and integration of disease elimination programs, to reduce fragmentation, improve cost-effectiveness, and better serve communities’ needs. For example, programs can leverage shared diagnostics, using the same sampling and testing platforms to diagnose multiple diseases efficiently (which not only reduces costs but also ensures timely and accurate diagnoses across various conditions). In short, experts at this consultation recognized the importance of integration at every level – health services, laboratory and diagnostic services, training of providers, information systems, and more6. This meeting served as the cornerstone of the Elimination Initiative.

EThis knowledge informed the Elimination Initiative’s Strategic Line of Action 1: Strengthening the integration of health systems and service delivery.

Need for stronger systems for knowledge and information exchange

Over the decades, as PAHO and Member States tracked diseases and conditions, they realized the need for strong data collection systems to effectively share and exchange information and knowledge. The 2015 Regional Consultation identified the need for a research agenda focused on overcoming obstacles-they pointed to the need for “immediately usable solutions in the field” that would help countries achieve elimination goals. They also pointed to the need for quality surveillance data6.

Without timely and efficient surveillance systems spanning all levels of the health system – from local to the national and regional levels – Member States cannot make informed decisions related to policy, financing, and services. Stronger data systems can help ensure that we know where the gaps are: we can see which groups are being left behind, which diseases are falling short, and where additional resources are needed. Technology is constantly advancing, and Member States now have access to more sophisticated digital health and data sharing systems. The Elimination Initiative is helping ensure that these systems are being strengthened so evidence can be used more effectively.

This knowledge informed the Elimination Initiative’s Strategic Line of Action 2: Strengthening strategic health surveillance and information systems.

Importance of addressing health comprehensively

Importance of addressing health comprehensively

Member States have learned over time that variations in disease burden are often linked to social determinants of health. Specifically, many diseases and conditions have their greatest impact on populations that live in situations of vulnerability, are marginalized socioeconomically, and/or experience difficulties in accessing health services. One such example is trachoma, which most often affects those living in extreme poverty. Its transmission is driven by social and environmental determinants such as sanitary conditions, hygiene, and overcrowding7. Another example is tuberculosis: crowded and poorly ventilated environments and undernutrition – all factors associated with poverty – are direct risk factors for tuberculosis transmission8. By tailoring interventions to specific groups, health systems can ensure that disease elimination efforts are inclusive, accessible, and responsive to the diverse needs of all community members, particularly those often overlooked by traditional healthcare systems.

In addition to considering social and environmental determinants of health, the initiative was informed by years of program data showing the importance of considering different stages of the life course. For example, pregnant women are at increased risk of severity of symptoms when infected with certain diseases like measles or malaria.

This knowledge informed the Elimination Initiative’s Strategic Line of Action 3: Addressing the environmental and social determinants of health.

Benefits of a multisectoral approach

PAHO is uniquely positioned to convene stakeholders and continue momentum towards disease elimination. Over the years, PAHO and its partners have brought together coalitions of scientists and technical advisory groups related to a range of diseases-from tuberculosis to HIV to Chagas. In addition, PAHO facilitates multisectoral collaboration among governments, funders, the private sector, communities, civil society organizations, and others. Among other benefits, this collaboration helps reduce the costs of supplies and vaccines for Member States. For example, through the Regional Revolving Funds (RRFs), PAHO improved access to the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV), which is crucial for preventing cervical cancer. Working with private manufacturers in the late 2000s, PAHO negotiated on behalf of participating countries to reduce the price of the HPV vaccine from more than USD 120 per dose in 2007 to under USD 10 per dose.9.

This achievement exemplified the impact of multisectoral efforts to improve the accessibility and affordability of essential health supplies for PAHO’s Member States.

This achievement exemplified the impact of multisectoral efforts to improve the accessibility and affordability of essential health supplies for PAHO’s Member States.

Other multisectoral partnerships within Member States also have proved essential to disease elimination efforts. For example, in the area of HIV prevention and treatment, multisectoral partnerships brought together diverse stakeholders including governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), businesses, healthcare providers, educational institutions, and faith-based organizations. These collaborations enabled a more comprehensive approach by combining resources, expertise, and reach to address various aspects of the epidemic simultaneously. Over the last few decades, these partnerships facilitated wider dissemination of prevention information, improved access to testing and treatment, and helped combat stigma through coordinated efforts across different sectors of society.

This knowledge formed the basis of the Elimination Initiative’s Strategic Line of Action 4: Strengthening governance, stewardship, and finance.

Barriers and gaps

The Elimination Initiative builds upon years of experience in improving health systems and fostering cooperation across different sectors. However, several obstacles could impede progress towards the Initiative’s objectives:

- Migration: The movement of people – both within and among countries in the Region – can significantly impact disease elimination. Key issues include the potential for disease transmission across borders, reduced healthcare access for migrants, lack of culturally sensitive healthcare services, and difficulties in tracking and managing prevention and treatment efforts in mobile and cross- border communities.

- The rise of noncommunicable diseases: The increase in noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) has become one of the most pressing issues facing the Americas in recent years10. Examples of NCDs are diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer, and chronic lung disease11. In addition to competing for limited funding, NCDs can often present complications to the treatment of communicable diseases, particularly chronic infections.

- Existing health inequities: Literature strongly suggests that groups facing social and economic inequalities are consistently at higher risk of communicable diseases12. Marginalized communities are more susceptible to communicable diseases due to a complex interplay of factors including limited healthcare access, poor living conditions, economic disparities, lower health literacy, and systemic neglect stemming from discrimination and lack of political representation. Further, when these communities are affected by these diseases, they can exacerbate conditions of inequality, leading to a vicious cycle.

- Stigma and discrimination: Groups that often face healthcare-related stigma and discrimination include LGBT individuals (particularly transgender people), indigenous communities, undocumented immigrants, sex workers, and those living with certain communicable diseases (for example, HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis), as well as a range of other groups. Stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings can hinder broader elimination efforts by discouraging affected individuals from seeking care (or not treating them effectively when they do seek care), leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment, reduced adherence to medication regimens, and incomplete disclosure of health information to providers.

- Impact of climate change: Climate change can impact the efforts of the Elimination Initiative in a number of ways. Changes in temperature, precipitation, and humidity can affect the transmission of vector-borne diseases. It can also lead to the emergence of new pathogens by altering weather patterns and habitats. Climate change can impact the range, period, and intensity of infectious diseases13, 14. Further, climate change can exacerbate conditions of inequality, which can add to the risk for communicable diseases.

- Human–animal–environment interactions: The elimination of zoonotic neglected diseases, like rabies, and the characterization of sylvatic reservoirs and vectors of epidemic prone diseases, like yellow fever and plague, require integrated surveillance and coordinated interventions. A One Health approach can address this.

- Resource constraints: Sustaining disease elimination efforts can be difficult in already resource-constrained settings. Funding can be siloed and stretched thin, and communicable diseases present significant challenges to already-strained government health budgets as they face a growing range of health threats, including the rising incidence of NCDs and the health impacts of climate change. In addition, much of the global agenda and funding has been directed to certain “high profile” diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria – while leaving others, like neglected infectious and zoonotic diseases, out of focus.

- • New communicable diseases, including COVID-19: As was the case globally, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and amplified the need for stronger health systems and services in the Americas. When new diseases emerge, countries often must divert resources and efforts to focus on the new diseases, offsetting progress towards the elimination of existing diseases15. Further, new diseases can often contribute to a “syndemic” – a situation in which two or more disease states or health conditions interact synergistically, contributing to an excess burden of disease in a population.

- Antimicrobial resistance: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens effective prevention and treatment of a range of infectious diseases caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses, and fungi (including many of the 30+ diseases included in the Elimination Initiative). Specifically, AMR reduces the effectiveness of drugs used to treat infections, potentially making previously manageable or curable diseases more difficult or impossible to control – and allows resistant disease strains to spread. This can greatly undermine progress towards elimination targets.

Opportunities

Despite facing challenges, the Region is also presented with many opportunities in achieving the elimination of communicable diseases. Integrating health services – through an emphasis on primary health care – is a priority for governments overall (beyond communicable diseases) but can be leveraged as countries work towards elimination of communicable diseases. Crosscutting capacity building strategies – including mechanisms like the RRFs –offer critical support in ensuring the timely and efficient distribution of medicines and health technologies within the Region. Relatedly, a focus on health sovereignty in the Region of the Americas is helping to strengthen regional production of vaccines, medicines, and public health inputs – which helps ensure access to these critical products.

Despite facing challenges, the Region is also presented with many opportunities in achieving the elimination of communicable diseases. Integrating health services – through an emphasis on primary health care – is a priority for governments overall (beyond communicable diseases) but can be leveraged as countries work towards elimination of communicable diseases. Crosscutting capacity building strategies – including mechanisms like the RRFs –offer critical support in ensuring the timely and efficient distribution of medicines and health technologies within the Region. Relatedly, a focus on health sovereignty in the Region of the Americas is helping to strengthen regional production of vaccines, medicines, and public health inputs – which helps ensure access to these critical products.

The growing recognition of community engagement and community participatory research offers potential solutions to current challenges, particularly related to meeting the needs of marginalized groups and creating demand of services related to the targeted diseases. Improved technology also presents an important and innovative tool for surveillance, treatment, integration, and disease management. As governments become more aware of social determinants of health, they can more effectively meet the holistic needs of individuals, helping to break the vicious cycle of disease risk among marginalized communities.

Also, the concept of the Elimination Initiative itself presents a great opportunity. “Elimination” is a strong message that can appeal to governments and politicians and present a way for them to show results and create real change. This can lead to interest and political commitments.

Finally, while the COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to health systems throughout the Region, it also presented unique opportunities. For one, it dramatically increased awareness of the importance of health to social, economic, and political stability. It also accelerated the uptake of certain innovations related to service delivery. This created unique opportunities to apply these innovations to future health challenges as well.15.

Click here to see the image in its full size.

References

- 1. Pan American Health Organization. An integrated, sustainable framework to elimination of communicable diseases in the Americas. Concept note. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2019. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51106.

- 2. Pan American Health Organization. PAHO Disease Elimination Initiative: a policy for an integrated sustainable approach to communicable diseases in the Americas [Resolution CD57. R7]. 57th Directing Council, 71st Session of the Regional Committee of WHO for the Americas; 30 September–4 October 2019. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2019. Available from: https://iris. paho.org/handle/10665.2/58139.

- 3. World Health Organization. Eighth report of the Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases (STAG-NTDs). Geneva: WHO; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/eighth-report-of-the-strategic-and-technical-advisory-group-for-neglected-tropical-diseases-(stag-ntds).

- 4. Pan American Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; [date unknown] [cited 16 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/social-determinants-health.

- Caffe S, Pérez F, Kamb ML, Gómez Ponce de León R, Alonso M, Midy R, et al. Cuba validated as the first country to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and congenital syphilis: lessons learned from the implementation of the global validation methodology. Sex Transm Dis. 2016; 43(12):733–736. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000000528.

- 6. Pan American Health Organization. Regional consultation on disease elimination in the Americas. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2015. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/regionalconsultation-disease-elimination-americas.

- 7. Pan American Health Organization. PAHO and Canada join efforts to eliminate trachoma in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2023 [cited 16 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/news/22-9-2023-paho-and-canada-join-efforts-eliminate-trachoma-latin-america-and-caribbean.

- 8. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Programme: social determinants. Geneva: WHO; c2024 [cited 16 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/globaltuberculosis-programme/populations-comorbidities/social-determinants.

- 9. Pan American Health Organization. PAHO Revolving Fund. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2024 [cited 16 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/revolvingfund.

- 10. GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

- Hambleton IR, Caixeta R, Jeyaseelan SM, Luciani S, Hennis AJM. The rising burden of noncommunicable diseases in the Americas and the impact of population aging: a secondary analysis of available data. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;21:100483. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100483.

- Ayorinde A, Ghosh I, Ali I, Zahair I, Olarewaju O, Singh M, et al. Health inequalities in infectious diseases: a systematic overview of reviews. BMJ Open. 2023;13(4):e067429. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067429.

- 13. Pan American Health Organization. Climate change and health. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; [date unknown] [cited 16 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/climate-change-and-health.

- Yglesias-Gonzalez M, Palmeiro-Silva Y, Sergeeva M, Cortés S, Hurtado-Epstein A, Buss DF, et al. Code Red for Health response in Latin America and the Caribbean: enhancing peoples’ health through climate action. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;11:100248. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100248.

- Espinal MA, Alonso M, Sereno L, Escalada R, Saboya M, Ropero AM, et al. Sustaining communicable disease elimination efforts in the Americas in the wake of COVID-19. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100313. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100313.